FIRESIDE No. 15 with Wilmot "Ray" Harmon

Posted on December 12, 2017 by Blake Leath

"DEFINING MOMENTS,

KEEPING COMMITMENTS

PAIN, COURAGEOUS

LEADERSHIP, EMPATHY,

BURNOUT, GRATITUDE,

BALANCE, MARGIN,

A LIFE WELL-LIVED

LEGACY, VISIONEERING,

AND STEPPING OUT IN FAITH"

• • •

I’m an organizational sociologist, strategist, writer, and teacher, but am—first, foremost, and always—a student of enterprises and those who lead them. In my 2007 book, Cultivating the Strategic Mind, I explored the transition from leader to visionary, creator, and architect of strategy. Today, I continue studying strategists and leaders but am increasingly haunted by what I see as a more fundamental, personal quest: understanding and improving the dying sub-disciplines of management, whether time, conflict, self, or life-management. Leadership gets a lot of glory, but management is the nuts & bolts practices of every day that gets it done. Fireside (which admittedly began as a series of ruminative 1 ½ to 2-hour one-on-one conversations with seasoned management executives reflecting on their life’s work) quickly evolved into dialogues about work within the context of life and life after work. This ricochet took me by surprise, but I found it an exceedingly pleasant one. After all, “Though we hire employees, we get people.” My sincerest hope now is that—in an oft-discouraging world—Fireside might prove a respite, a source of light, warmth, energy, encouragement, safety, nourishment, perhaps even inspiration in your own career or life, whether at home or out in the big, bad world. Around the fireside at the end of the day, it’s clear that we are all in this together, and everyone has a story worth sharing and hearing. You will be the ultimate arbiter, of course, but I predict we shall learn a great deal about management, yes, but even more about ourselves and this enterprise we call life.

• • •

Today’s guest is Wilmot “Ray” Harmon.

Ray is Lead Pastor at City Church in Plano, Texas. Born and raised in Liberia, West Africa to a respected, influential, multigenerational political family, Ray and his brother miraculously escaped execution and fled into neighboring Sierra Leone where he and his family lived in exile for three years. In 1993, Ray and his family were granted political asylum and moved to the United States.

After immigrating to the U.S., Ray enlisted in the United States Army and served with the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) at Ft. Campbell, KY, and Oklahoma National Guard. Upon discharge, Ray served in leadership positions with HF Controls (a subsidiary of Doosan Heavy Industries, Korea) and Peerless Manufacturing Company.

In 2004, Ray began a career in the ministry. Ray has served as an Associate Pastor with two North Dallas churches overseeing multiple facets of ministry including coaching, leadership training, and curriculum development. Ray is also the co-founder of IDLeaders, a turnkey leadership consulting and marketing firm dedicated to empowering the local church and its leaders through individual coaching and group training seminars. Ray is also a conference speaker, itinerant minister, and principal of HHC Global, which exists to serve individuals and communities in emerging nations.

Ray enjoys playing and watching basketball (a die-hard North Carolina Tar Heels fan), songwriting, politics, blogging, movie-going and spending time with his family.

He and his wife, Wendy, have two children, Nia, 13, and Levi, 8. The Harmons reside in North Dallas.

Blake Leath: Thanks for hanging out with me today, Ray. You’re currently leading a church, a church that you began several years ago. Can you talk to us about your life before that? What led you, in the first place, to begin a church, or what called you to a life of ministry? “How do I know who or what I was designed to be?” is a big question for a lot of people, so I’m curious to know how you think we come to know whether we’re living the life we were created, designed, or perhaps even destined to live.

Ray Harmon: Sure, I can speak to that, but let me just start off by saying thank you for affording me the opportunity to share my thoughts with you. I’ve been reading the FIRESIDE series every week, and I think what you’re doing here is fantastic. On behalf of everyone who’s joining and reading, thank you.

Blake: Thank you, Ray.

Ray: My story really begins halfway across the world, in Liberia, West Africa, where I’m from originally. I grew up in a family that was influential in politics and business, and a defining moment for me, a watershed moment in my life, occurred in late 1989-early 1990 with the advent of the Liberian Civil War. If you know anything about African politics, it can be pretty brutal, pretty bloody, and the Liberian Civil War was no different. My family were, automatically, a part of the sitting administration, and, so, naturally with the Civil War and the infiltration of rebels who crossed over the border into Liberia, we were considered a target. My family and other political families were targeted, and we really saw a lot of carnage; I saw humanity at its worst. But it was also a defining moment for me, personally, because I had this particular encounter. It’s a rather long story, though, Blake. Do we have time to go into this?

Blake: All the time in the world, brother, all the time in the world.

Ray: Okay. At the time, I was 18, and my brother was 20. And we had this encounter with some freedom fighters. They preferred to be called freedom fighters, not rebels. We had been arrested and held for interrogation. My brother and I were separated from our parents. My parents had already made it across the border into neighboring Sierra Leone. My brother and I, because we got separated from them, are behind, and now we find ourselves behind rebel lines confronting young men—children, really—soldiers who are our peers, late teens a lot of them, the only difference being that we were the sons of politicians, and they were armed with AK 47s, M-16s, and RPGs. They begin the interrogation process, and one of the young men is visibly agitated. He’s insistent that they’re gonna hold us, keep us there, not let us go. My brother’s name is Josh so, growing up, everyone called me Junior. They say, “We’re going to hold Josh and Junior until our commanding officer comes, and he’ll give us the order to execute them.” They threw us into this makeshift cell in the center of the building we’re in, a sort of storeroom or something, in the middle of this abandoned filling station. This room, Blake, is pitch dark, so it doesn’t matter that it’s the middle of the day. I couldn’t even see my hand just a few inches from my face; that’s how dark it was. Outside, there’s this commotion. There’s this kid who is insisting that they’re going to keep us, that they’re going to give the order to execute us. in that moment, Blake, my brother and I are 18 and 20 years old, man, and we started to say our goodbyes. We thought our death, our execution, was imminent. There was no way out of it.

Blake: Oh, Ray.

Ray: Probably about 45 minutes to an hour later, it gets eerily quiet, and then there’s this conversation outside. The one young man is still belligerent, but there’s this calming and reassuring voice that seems to, you know, get him to stand down or something. And a few minutes after that, I can’t make out what they’re saying, but then someone comes in, unlocks this door—which had a latch and a padlock. They unlock it all, bring me and my brother out, and present us for this young man who is, at most, 25-26. He asked my brother and me, “Do you know who I am?” We say, “No sir, we don’t.”

He introduces himself, and begins to tell the story of how, as a young man, he and his mother would walk past our home. He says my mom would stop and speak to his mom, who was just another woman selling oranges in the local market. Sad to say, but in typical African culture, a person of prominence—in this case, my mother—would not generally interact with people of lesser means. But this young man, nearly 20 years later, is remembering and sharing this story with us.

Blake: About your mom?

Ray: About my mom. About the fact that she spoke to his mom. But the other thing that stood out to him was the fact that she spoke in his mom’s dialect, which, coming from Liberia, if you are a person of prominence, well-to-do, you only speak English, and so it blew his mind that this lady, wow, this lady is speaking in my mom’s native tongue. He tells us he remembered that he was hungry, and had nothing to eat, and he said my mom reached into her pocket and pulled out a couple of dollars, gave them to his mom, and took a few oranges out of the large pan on her head (because that’s how women who sold vegetables and fruit in the market…they would have these large pans on their heads). So she, my mom, reaches into the pan and takes out a couple of oranges and gives him some candy, too. And that was the memory that he had of his encounter with my mom, years before. He shares this memory with Josh and me, and then he says, “Because of your mom’s kindness, because of your mom’s kindness, I’m going to let you and your brother go.”

Blake: Oh, Ray.

Ray: I share that story, Blake—and I know it’s long, so I apologize for that—but I share it because that one moment in my life has framed everything that followed, from my feeling called, and my ministry, to framing how I relate to others. My mom’s random act of kindness, that this young man chose to pay forward, is the reason my brother and I are alive today, the reason our family is intact, the reason you are speaking with me. If not for my mother’s kindness, none of this would be possible. And so, I committed from that moment forward to dedicate myself to the service of others in any way that I possibly could, to improve someone’s life, even a stranger’s life, even if it’s just a handshake, a smile, or a hug. My desire from that moment forward has always been to improve the quality of life for someone. What I do in ministry is just the vehicle for a much bigger purpose, which is helping and empowering people, so that’s how I started my journey in ministry.

Blake: What a tremendous testimony, Ray. Really tremendous.

Ray: You know, they say there are no atheists in the trenches, Blake, and my brother and I have both dedicated our lives to the service of God. “God,” we prayed, “if you get us across this border—and we don’t know how you’re going to do it—but if you get us across this border, if you reunite us with our family, our lives are dedicated to you.” And that’s when the commitment began, right then and there. So Blake, to those who ask the sort of questions that you posed to me — “Why on earth am I here?” “For what purpose was I created?” — they are not alone. Here’s what I believe: The who that I am, and what I was created to do, is not for me to decide, but it’s really for me to discover. What that means, Blake, is that who I am and what I was created to do, what I was created to accomplish is God-appointed, not self-assumed. Ultimately, God had this plan, this divine design, and He has thought it out, and my part is to simply discover what God has already decided.

Blake: I love that, Ray; that’s really beautiful. Then what happened? How did you find yourself here?

Ray: Our family, reunited, came to the states together. After what we’d experienced, the rest may sound rather prosaic, but here we go: We lived in New Jersey, and I had the privilege of serving with the United States Army for four years, with the 101st Airborne Division stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. I learned so much there, and after my service I went off to Bible college, a small school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and then I accepted an invitation for an internship in Plano, Texas, and that’s how I landed in this area, about 17 years ago now. But then, ultimately, in 2010-2011, I made the decision—with my wife’s support—to plant City Church in Plano, and it’s been a glorious six…almost seven years.

Blake: I have a dozen questions, but lemme start with a pragmatic one: What’s your family’s relationship with Liberia today? Is there any connection?

Ray: My mom and dad live here, now, in Columbus, Ohio, but yes, they went back home to Liberia for about a year, then my dad had to return to Columbus for an emergency surgery, and they stayed. I’ve been back three times, as there were opportunities to equip and empower some people, and just some really neat opportunities that we were pursuing there at the time. They didn’t fully materialize, but yes, the opportunity to go back home, and actually re-establish our roots there, and really get involved in what’s happening, societally, that opportunity is still there. In fact, my older sister, Sharon, travels to Liberia every six months. She works as a nurse in Minnesota, and then travels to Liberia and lives there for about six months each time, helping people there. So yes, the relationship with Liberia is a good one; it’s a healthy one.

I think the Civil War, which continued unabated for about 14 years, as painful as it was, corrected some of the ills that had existed for a very long time in our nation.

Blake: Can you tell us more about Liberia?

Ray: It’s crazy, Blake, that Liberia was founded by freed men, freed slaves, emancipated slaves who were repatriated to Liberia by a Quaker organization called the American Colonization Society. This was the early 1800s, maybe 1822, and in 1847, Liberia became an independent republic. The unfortunate thing about our history is that these freed men—who were in the minority—imposed some of the same mistreatment on the indigenous Liberians, who were the majority. For over a hundred years, we had what was called the Americo-Liberian Minority. I would be considered an Americo-Liberian because my name is Harmon. Blake, I went to school with guys whose last names were Cooper, Tolbert, Johnson, Williams, Jackson…guys who were all Liberian, born in Africa, but that’s our heritage. We are the sons and grandsons, the progenies of freed men from America. But I also went to school with guys named Zayzay and Karnga, indigenous Liberians who, unfortunately, were excluded from political leadership. There was so much inequality and injustice; that’s kind of what led to the unrest in Liberia, beginning with the coup d’état in 1980, and then culminating with the Civil War that started in 1989. But the relationships right now in Liberia are very good. A lot of those injustices and that dichotomy that once existed between the Americo-Liberians and indigenous Liberians have been addressed, resolved, and the future is really bright, Blake, and that’s where I see an opportunity based on my own experiences, the things I’ve learned, and a new perspective to be part of making a difference…to bring enduring peace and enduring healing to Liberia.

Blake: And we absolutely must talk about your mom! She sounds like an amazing woman, and yep, she did nothing short of saving your life.

Ray: Understanding my mom, and how she’s lived, I think, can be traced to the fact that—even though she married into a family of influence and affluence—she was actually, as they say, “from the other side of the tracks.” When my dad met my mom at university, she was a single mom. In fact, my paternal grandmother didn’t even want my mom and dad to marry; she had someone else in mind that she thought would be better suited for my dad, who was also from a prominent family, but my dad met my mom and fell in love and married her.

Blake: A tale as old as time.

Ray: Several years later, I would meet my maternal grandmother. One of the things for which I was unprepared was the fact that she was illiterate. Never learned to read or write. I really believe, Blake, that when my mom saw the market woman taking her wears to market with her son who was hungry, I think she really saw her mom in that woman. I believe she saw herself in that boy who, many years later, would be the reason that I’m alive today.

So even though my mom, who—by the providence of God met and married a man who adored her, who was a man of means—she never lost sight of herself, where she came from, and the value of all people.

Blake: And this teaches you…what…?

Ray: That everywhere I go, regardless of who I meet, I will esteem them as valuable and precious, that people matter to God, so people matter to me. And because my mom had such humble beginnings, such very humble beginnings, I know in my heart of hearts that it shaped and formed how she responds to people, all people, and always has.

One of my mentors would say, “Ray, be careful how you treat people on your way up, because they’re the same people you may meet on your way down.” That’s true, and it’s also the reason I’m alive. Our family toppled from a position of influence, and it was my mother’s grace—and a young man who remembered it—that saved her sons’ lives and, in the process, will be paid forward forevermore. So this is the backstory to what happened on that fateful day behind rebel lines: My mom never lost sight of her roots, where she’d come from, and she treated people—all people—with love, respect, and dignity.

Blake: I don’t know whether we’ll get into politics or not, Ray, but I’ll share a memory from 2016 in which a debate moderator asked Hillary Clinton whether she saw any redeeming qualities in Donald Trump, to which she responded—and I’m paraphrasing from memory here—"He appears to take care of his family.” She bit her tongue so hard I thought half of it might fall on the carpet! I know that as human beings swirling around in the human condition, we sometimes come across people for whom we have little empathy, in whom we struggle to find something redeemable when, in truth, we only see people in part; we are in no position to judge, and if everyone knew our own failings, we’d probably live in a collective fetal position and never leave the house!

I’m discouraged by the vitriol and hate, and the glee some of our leaders take in others’ downfalls and demise.

Ray: As a result of my parents’ influence, I was fortunate—at an early age—to develop a set of core values that have guided my entire life, its entire trajectory, and certainly all my decisions. One such core value is this: I will never make my light shine brighter by blowing out another man’s candle. I honor this value every day, in every interaction, regardless of the person’s proclivities or disposition, and no matter their flaws or idiosyncrasies. I’m simply never going to make myself look better by down-talking or downplaying them. I choose to believe that—no matter the circumstance—I will find the good in everyone.

Jesus taught this amazing principle. He said, “Before you take the stick out of your brother’s eye, take the log out of your own eye,” and I think one of the reasons Jesus described it this way is because eyes are delicate. We know this all the more today, and how delicate eye surgery is, in particular. What I believe is that if we deal with the log in our own eye, our own shortcomings, what we may realize is that there probably wasn’t a speck in my brother’s eye after all. Maybe what I thought I saw in my brother was a result of the log that was in my own eye…that distorted my vision, that made me see my brother with a speck that really wasn’t there.

As the pastor of a church, I’m charged with the responsibility of being a purveyor of truth, so the way I balance all this out—what may be in my own eye, and what may actually be occurring in another’s life—is to not ignore a wrong, but to speak the truth in love. A truth, without grace, is mean. But grace, without truth, is meaningless. A lot of times, what we do is speak the truth—and you talk about the vitriol in America today, and in Congress, and in our political landscape—and what we both see and hear is a version of some people’s truth, but there is absolutely no grace in it. It’s mean spirited. But the converse is also true, that if I’m continually giving grace-grace-grace, but am reluctant to speak truth to the real issues and the hard issues, that’s meaningless. The opportunity, therefore, is to strike that balance between grace and truth. The scripture says in John 1 that Jesus came full of “grace and truth,” and I think we have an opportunity in our nation—and in our world—to rediscover that balance.

In the case of Hillary Clinton, I think a lot of things have been said of her, and she—like any of us—wants to take the high road. That’s grace, but then also speaking the truth about what she thinks is wrong, you know?

Blake: I know, yes; I know. Great point, and a great reminder for all of us, that we need to be truthful, but graciously so.

Hey, let me ask you a question: I’m sure you’ve shared your Liberian story many times throughout your life, particularly as a pastor, because it speaks volumes to living a right-minded life, but what questions about that story have people never asked you…that you wish they would ask?

Ray: Wow, that’s a big question, Blake. Lemme think about this. I think I would say that, for me, the answer to that question would be Why isn’t there more bitterness or animosity toward the people who took so much from you, and took so much from your family? And I think the answer to that goes back to those values, decisions, and choices that we make daily and, for me, one of those choices is the choice to forgive.

Something I say to our leaders in the church is that, “One of the keys to being a great leader, and leading for the long haul, is pain management.” The first time I said this, they looked at me with this puzzled look on their faces. Pain management? What does pain have to do with leadership? When it comes to leading others, and leading well, pain is inevitable. It touches everyone’s life. My experience in Liberia was harrowing, it was horrific, it was painful, but my response to that pain, ultimately, is the thing that determines my longevity — my thriving beyond survival.

One of the ways I think about it, Blake, is like comic book theology. I know you’re a reader, and you’re a historian, so with comic books—surely you’ve noticed that just about every villain starts out as a victim. Think about the Joker, or the Penguin. They each have a backstory, where they’ve experienced pain, some kind of trauma, some kind of rejection. The thing about pain is this: People who don’t deal with their pain make life painful for others, so people who see themselves as victims often wind-up victimizing others.

Of all the questions I have been asked about that story, I’ve never been asked, “How did you deal with your pain?”

Blake: And yet how you’ve managed your pain has made all the difference in your life.

Ray: I have several friends, several close friends, who also survived the Civil War there, who have vowed to never step foot in Liberia ever again, because the pain of what they experienced is just too great. Even though all the conditions in Liberia right now point to the fact that we are a reconciled nation, that we are a restored nation — and I’ve been back three times and my sister goes every year — these friends have processed and framed their experiences in a radically different way than how we have. So, thank you for asking the question, Blake, because I think that’s a fantastic and profound question. No matter where we are, no matter who we are, at some point in everyone’s life we are all brought to our knees. We can’t avoid pain, because that simply brings more pain. As leaders, as human beings, as managers of others, we can get stuck in a particular place around an event, and often because we’re unwilling or afraid to push past the discomfort, through the pain and its acknowledgment, and never able to move past that place in our lives. Only by completing my grief cycle can I continue to grow, and I cannot grow beyond pain that I’m unwilling to confront.

Man, I’ve never thought about this stuff, Blake; I’ve never thought about that question. Thank you for helping me consider it in this moment, because it may help me, or help my friends who—and I pray this will happen—may read this interview and come to terms with every villain beginning as a victim. If they don’t deal with their own pain, they ultimately make life more painful for others.

Blake: I think you’ve succinctly articulated something that could prove helpful for a lot of people, Ray, not just your own friends.

Ray: And I don’t want it to sound cliché or trivial, like, “If life gives you lemons, make lemonade,” but it’s been my own experience that our Civil War afforded me the opportunity to empathize, to appreciate the plights of people who are marginalized, disenfranchised, who—at some point—said, “Enough is enough.” Because we all have this pain threshold, right? That point at which our pain becomes too much to bear, and it has to be expressed in some way. That’s what happened in Liberia: A large segment of Liberian society had been mistreated for a hundred years, so oppressed, that the only logical reaction was resistance and rebellion. I understand why they felt that way, so now I want to be part of the solution.

I’m sorry for going on and on, Blake, but here’s another connection I’m making: One of the things I find so fascinating about the parable of the good Samaritan is this tiny phrase, sort of tucked in between several verses, that talks about the priest—who saw the man who had been beaten and robbed—and just walked right on past him. And the Levite, who walks right on past him. And then we’re introduced to the Good Samaritan, and this tiny scripture that says, “Seeing the man in his condition…” I think, sometimes, Blake, as humans, and as leaders, we can maybe sometimes identify a problem…Oh, there’s somebody who’s been beaten and robbed. We can sometimes maybe even label what the problem is, but very few of us go where that person is…and that’s the difference between the Good Samaritan and the two men who preceded him.

I think the Liberian Civil War gave, not just me, but so many Liberians, the opportunity to go where these people were. It’s not enough to stand across the street and say, “Oh, yeah, there’s a guy that’s beat up; I see him.” We have to push past our discomfort, be willing to walk across the road to where these people are, and identify with them in their struggle and in their pain. So thank you for asking that question.

Blake: Well, I just know that I share a lot of stories, too, and sometimes it surprises me that people don’t ask what appears to be the most obvious, unanswered question. Thank you for sharing what you’ve shared. Not only is it insightful, and powerful, but it’s also operational. I think each of us can not only learn from it, but operationalize it right away by reaching out, by crossing the road.

Ray: Yeah, I’ve never had anybody ask me, “So why don’t you have PTSD, or why don’t you hate Liberia?” The answer is the same: I’ve learned to manage my feelings about them, to repurpose them, and to put those painful experiences in their proper perspective.

Blake: I’ve got tons more questions, so let’s keep going. I guess my next observation would be that you’re not alone; there is so much grief in the world, whether it’s people struggling to recover from the loss of life and limb following a natural disaster, to those who struggle with their leader or our President, to the unrest in our nation—whether something symbolic, like taking a knee—or being the victim of harassment, or harassment in the workplace. Joe Brouillette spoke at length about grief, as did Susan Thoma, and I also can’t help but think of the work of Louis Gates and Bryan Stevenson, who have each devoted the majority of their adult lives to right societal wrongs.

Ray: For the past week or so, I’ve been hanging out in I Chronicles, chapter 4, verses 9 and 10. It just records the story of this obscure character named Jabez. It’s tough to read, ‘cause it has a lot of genealogy (like 40 generations deep, or whatever), and then all of a sudden it’s interrupted with these two tiny verses. We hear about this guy named Jabez, whose name means pain, and who is more honorable than his brethren. And then he prays this radical prayer, saying, “God, I want you to bless me indeed.” Sounds pretty self-centered, or selfish, right? But there’s so much power in that prayer. The second thing he prays is, “that your hand would be with me.” The third thing he says is what I spoke of before, and perhaps that’s why your question resonated so much with me, because it makes the tumblers fall into place. Jabez prays that God would bless him indeed, that God’s hand would be with him, and the third thing he prays is, “that you would keep me from evil, that I might not cause pain.”

Blake: Wow.

Ray: I know, right? It’s so cool, because Jabez is really praying that God would help him get his relationships right, because these are ultimately the source of our greatest pains: human to human, friend to friend, family to family relationships. We could hang out there forever, man, because it’s just so true. Some people, particularly with regard to family, come from an environment that might be toxic, so they get completely marinated in these juices. I think a lot about what juices am I marinating in, because it helps me reframe and reprocess my life.

Blake: I love that, Ray; please, keep going. Preach!

Ray: Here’s the way I think about it, the Four E’s.

Blake: Okay.

Ray: My environment determines what I’m exposed to. What I’m exposed to determines my experiences, and my experiences will determine my expectation(s) of myself and others, be they good or bad. So think about this for a second. My environment, Liberia, exposed me to a completely different set of experiences, which, in turn, shaped my expectations. This creates what one might describe as his or her “inner script.”

Blake: Self-talk.

Ray: Right. And if we’re not careful, what we marinate in—which may be toxic—becomes normalized. If we don’t manage the ingredients carefully, it can spoil the meat. So when Jabez prays, in effect, keep me from evil experiences so that I won’t be the cause of pain, I think that’s really powerful, because he’s aware of the marinade. We can’t un-ring a bell, un-spill milk, or un-marinate a steak. But God can renew our mind, and Jabez knows that God can also keep him from harm and, when the day comes that he does experience harm, God can help him reframe and repurpose it, as He did for me.

Blake: There are a lot of hurt people out there, and anger, and division. I worry it will get worse, not better.

Ray: I think we sometimes want to sanitize the truth, the harsh realities, but all we can really do is speak openly, honestly about what’s happening, and do so with grace. That’s part of the challenge. Life isn’t as simple as clinging to some automatic response. It’s more complicated than that. How do we love, and not judge? Accept, without condoning? There are some conversations that are uncomfortable, like people protesting the national anthem, or Black Lives Matter, but the cycle perpetuates if we don’t root it out at the bulb, so these are the sorts of conversations I’m talking about, that allow people to express their anger, get clarity, and move forward.

Blake: [Sniper] Chris Kyle’s widow, Taya, weeks ago now, said, “Get off your knees and get to work.” At some point, our country has to move beyond symbolism and mobilize. I feel like we’re running from things, like healthcare, but I don’t know what exactly we’re running to.

Hey, let me ask you a question. Have you seen that Leah Remini show on A&E, the Scientology stuff?

Ray: I know about it, but I haven’t seen it, no.

Blake: When you described marinating, I can’t help but think of second and third-generation Scientologists, whose parents or grandparents were recruited off the sidewalk decades ago, and these kids now know nothing outside of it. They’ve grown up in it their entire lives. All they know is Scientology. She’s in season two now, and it’s increasingly powerful. People are coming out of the woodwork, and to hear their stories of indoctrination, total inculcation, generational pain, and L. Ron Hubbard’s practice of shunning and destroying people who disagree…it’s just insanity.

Ray: Hurt people hurt people, but the courage of just one person can make all the difference in the world. It gives others permission to be courageous.

Blake: Like we saw following Harvey Weinstein, scores of people now coming forward with their stories of abuse.

Ray: Exactly. I remember runner Roger Bannister, the year he shattered the 4-minute mile. Everyone thought it was impossible, but once he achieved it, it was like he gave everyone else the courage, or permission, to break it. I think it takes a lot of courage for someone to take a knee, or whatever it is they do symbolically, but if it gives other people permission to come forward, to tell their story and, in the process, receive healing, then maybe it’s not our place to be the lid on their life.

As a leader, I don’t want to be the lid on what others can accomplish, or what others can dream, or what others can be, or what others can become. I’m starting to realize that the more courageous I become, the more courageous the people who respect or follow me will become. The more I play it safe—and this goes back to Thomas Aquinas, who said, “If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve his ship, he would keep it in port forever”—so I think a lot of people live in that place where they build these magnificent vessels, but we say to ourselves there’s a storm out there, there’s a tempest, so I’ll just stay right here in port. The courageous leader, on the other hand, says, “I designed and built this seaworthy vessel, so let’s sail!” Yes, there will be some storms, and yes, there will be turbulent waters, and yes, there will be a tempest, but, man, I’m going to live courageously! I’m going to do things, I’m going to dream things, I’m going to attempt things that might be a little bit risky, because all faith is divine risk, so I’m going to do it anyway.

In the army, we would go on our runs. It could be a 2-mile run or a 3, 4, 5, or 6-mile run, and the platoon sergeants would always assign a pacesetter. The pacesetter would be the person standing or, yeah, the person who was in the far left rank of the formation. So if the platoon sergeant wanted to go on a really fast, up-tempo, brisk run, man, he would pick a pacesetter who was fast! But if he just wanted to go on an easy run, he would put somebody in charge who wasn’t a strong runner, because they set a slow pace for the entire platoon. I think sometimes in leadership—and Brené Brown would say, “Dare greatly,” that if we’re not daring greatly as the pacesetters in our organizations, for the people that we’ve been called to lead—it becomes the lid on how fast we can run, how far, how much we can achieve, how much we can innovate, how much we can create. Ultimately, how much we can become.

Blake: Law of the Lid. John Maxwell . That’s great stuff, and a great read for people.

Ray: I met with a church planter just yesterday, and he asked me, “What’s the one thing you’ve done in your ministry that’s gained you the most traction?” and my answer was, “Lead courageously.” Sure, caution is a good thing, but so is instinct, and there are times you just have to trust your gut and leap. I find, almost often, that there was this untapped potential, this momentum, almost as if people were holding their breath, and when you step out in faith, courageously, it sparks people.

So Leah Remini, as you’ve described her, seems to have leapt out in faith, taking on a very powerful entity.

Blake: Absolutely. Scores of lawyers. A policy of harassment and fear-based tactics. Joan of Arc, taking on the establishment.

Ray: Exactly.

Blake: Let’s return for a moment, though, to where we began. When you and Josh were sitting in that dark room, and you promised your life to God in exchange for your freedom…

Ray: Right…

Blake: You kept your promise. I know a lot of people who have made similar promises, only to break them. You’re such a full human being, perhaps, in large part, because you are His human being, but I wonder about your courage — perhaps a sense of sacrifice — that you were willing to forsake all you knew and trust in Him. Where does that sense of conviction come from? Why is it that some people make such promises and break them, and you kept yours? I love that quote from Teddy Roosevelt, by the way, in response to a question about what made him a successful President: “I made few promises, and I kept them all.”

Ray: Wow; that’s so good, Blake. Yeah, I guess the first thing that comes to mind immediately about what has sustained those commitments would be gratitude.

I think when we stop being grateful, when we stop being thankful, when we stop counting our blessings, we begin to lose our appreciation for everyday miracles. We begin to lose sight of the fact that, in my case, at least, if it had not been for the providence of God, I would not be here today. It’s so easy over time to lose sight of such things. Just look at the Israelites, who did so all the time! God would provide manna, he would provide quail, he parted the Red Sea, and somehow they found something to complain about! So, cultivating a lifestyle of gratitude, and appreciating all of life’s moments — even the imperfect moments, even the painful seasons, even the barren chapters of our lives — we must appreciate the good in all of it. I think that’s what sustained me, this idea of never forgetting, this idea of remembrance, and that was the tradition for the nation of Israel. When God performed a miracle, or did something profound, or special in the nation, they would build an altar, build a memorial.

One of my favorites is from 2 Samuel 7:10, where scripture says that David built an altar. He called it Ebenezer (which means, “stone of help”), saying, “Thus far the Lord has helped us,” and so I think — for me again — just remembering where I was, and all that I have become, is only by the grace and providence of God. I think if we cultivate that attitude of gratitude for the little things, even the jobs we have, the roof over our head, and cultivate appreciation for the things that we do have, our lives are lives of plenty. Paul gives us that lesson in Philippians, when he says a number of things about contentment, but then he talks further about it in 1 Timothy, when he says, “Godliness with contentment is great gain.” I think, sometimes, our desire for more, our desire sometimes for better, makes us lose sight of the things that we already have. We trade contentment for covetousness, and our gratitude erodes. In those cases, yeah, it makes it a lot harder to honor those commitments, and to keep our promises, because we treat people—and things—as little things, like commodities. We take them for granted. So, if you were to ask me, and you have, I would say the key to honoring our commitments is gratitude. I’m thankful for every good thing that I have, and for everything that I’ve experienced in my life, because it’s made me who I am today.

Blake: I saw similar gratitude on 60 Minutes this past season, when they interviewed Senator John McCain. What a powerful interview. That brain tumor he has, a glioblastoma, will surely be the death of him—as it is with 99% of those who get it, including Beau Biden and Senator Ted Kennedy before him — but when they asked McCain about his current attitude, he said, “Mine is an attitude of gratitude,” that he’s lived a wonderful, blessed life, and that he aims to finish strong. He said he would stay engaged until the bitter end, and then he quoted Duty, Honor, Country: “That’s how I was raised, and that’s how I’ll die.” So classy.

Ray: He’s a great role model, yes. A life of no regrets, of leaving it all on the field, and what legacy. My goodness. I’m always mindful of legacy, because once we decide how we’d like to be remembered, it governs how we live. I want to be remembered as a great husband, authentically, so that when Wendy thinks about Ray Harmon, she says, “That man was a fantastic husband.” And I want my kids to remember me as a great dad. My legacy informs how I live today, and I’m confident that if I can live consistently, it’ll be a life of no regrets.

One of my favorite quotes is, “The best way to get to the future is to create it.” Now, admittedly, we can’t predict everything, but we can decide—and choose—how we want to show up in this life, and how we want to live it. John McCain clearly has his eyes on the right things, like Duty, Honor, Country, and these are wonderful examples of timeless values, in the same way every contribution we make to our family outlives us, because it lives on through those who succeed us, who follow us, and who carry on our good works in His name. It’s the only way I know to live a life that’s truly rewarding and fulfilling.

Blake: Speaking of legacy, can I tell you a quick story of my own?

Ray: Of course; I’d love to hear it.

Blake: I’ll make it short, because it could be really, really long, and this is your interview, but when I was a boy, I just loved the martial arts. I read and watched everything I could get my hands on, went to tournaments every month, and took tons of lessons here, there, everywhere, but I had this one particular instructor for a decade, 1978-1988. Later, I went off to college. When I was home, visiting my parents, I would always make an effort to swing by and see him. Fifteen years later, he died. I can’t remember how I heard, but I knew when and where his funeral would be, so I flew home again to attend, because I didn’t want the church to be empty. I wanted to be present and represent. I showed up to the church, and the parking lot was full! I circled and circled, and eventually had to park down the street a couple blocks, and across the street! I walked in, and there must have been 600 people in a church that held 300. Grown men, young men, people of every sort and stripe were there, and several went to the front, knelt before his casket, and laid their black belts at the base of the flowers surrounding his casket. I thought to myself, “I thought I was the only one,” when it was clear that he had treated everyone…special. That’s legacy, and testimony. When I exited the church, there were dozens of people outside, sitting on the hoods of their cars because they couldn’t get in.

Ray: Oh, man. Just hearing that gives me goosebumps, Blake! James Baldwin, the African-American poet/playwright/author said it this way: “History, I contend, is the present.” Tomorrow is being made today, in the here and now. I think legacy is exactly that. These moments, these relationships, they outlive and outlast. I think just understanding the power of time is huge, because we are stewards of the here and now, and are hopefully using it to serve others. I think that’s where we began this interview, with the idea of serving others—in the same way my mom did, in the same way I hope my ministry does. And for you, I think what you do as a coach, as a leader, as a strategist, is a ministry. Any time we serve others, we find our calling, and our fulfillment.

Blake: That really resonates with me, and thank you for saying it. I once taught a grief class in a closing manufacturing facility, and an older gentleman approached me at the end of the day and put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Thank you, young man, for ministering to us.” He had tears in his eyes.

Ray: That’s it.

Blake: I get a lot of people who approach me and ask, “Why do you work so hard?” I do work hard, and there are entire years that sometimes feel really difficult, like more than I can sustain, but often it doesn’t feel like work at all, because I love it so much, because it’s so personally meaningful to me, and so professionally gratifying. I’ve heard golfers say, “Once you get a taste of that cup, you’ll keep coming back for more,” and I feel the exact same way. Once you’ve witnessed a demonstrable change in a person, and felt that you’ve pulled them back from the brink, or perhaps pointed them in a better direction, you can’t help but keep coming back for more, no matter how personally difficult or exhausting it may be.

Ray: Do you have a philosophy for living? Of life?

Blake: I don’t think mine’s much different than yours, though it’s certainly less dramatic! Primarily, the thought that recurs to me decade after decade is I want to die empty. Like what you said about McCain, I want to leave it all on the field. I don’t want to feel like there was a book in me that I never wrote, or a series that I never began, or a class that I never taught, or a soul that I never impacted because I withheld ideas that might have been exactly what they needed at the time. To the extent I can, I want to express those things, and help others live their very best possible life, and particularly in service to a mission or purpose greater than themselves, whether it’s as a federal employee, or an executive, or an operator in a manufacturing facility. It makes no difference, as long as they approach or achieve their best possible self in service to a greater calling or purpose. And particularly with dignity and integrity.

I know you have a lot on your plate, Ray. You’re a husband, a father, a church leader. Do you have any advice for us regarding balance? How do you manage the many responsibilities on your shoulders?

Ray: I’m still learning, but hopefully I’m getting better at it! Wendy and I have been married nearly 17 years, and this month we’re taking a trip to get away, and to recalibrate. Get in sync. Make sure we’re working in tandem. There are rhythms in life, and I want to make sure we’re not going it alone. Early on, there were things that I thought I had to do alone because, well, that’s what I do, but when we look at the model that God gives us in Genesis, it says, “It was not good for man to be alone,” so he created Eve. Adam isn’t God. No man is; no man is suitable or comparable. Eve is a completer, but not a completer of Adam, a completer of Adam’s purpose. In the same way, Wendy complements me, but, more importantly, when we work as a team, Wendy is the fulfillment of what I’m supposed to do. Our roles are different, because our skills are different, we are different, but together we are balanced. That’s the way God designed it, so our trip away will be to make sure that in everything we do, we do it synchronized.

Blake: That’s great; thank you.

Ray: You’ve described capacity a bit, Blake, when you talked about wanting to die empty, of leaving it all on the field, and capacity is one of the key things that we talk about in premarital counseling. We approach it by asking our betrothed, “Can you grow with me?” The idea is to grow together, not drift apart. I heard an Australian billionaire give an interview recently, and when asked, “What’s the thing you appreciate most about your wife,” he replied, “The thing I appreciate most about my wife is that she has adapted to the nine men I’ve become over the course of our marriage.” That’s a capacity thing, and a growth thing. Balance begins by being in sync, because we can’t do our portion if the other person isn’t doing theirs. It’s complementary.

The second thing we have to realize is that we can’t be all things in all seasons. Each season in our life has different demands, and we have to adjust accordingly. I think sometimes, as humans, and as leaders and managers, we don’t shift gears to keep pace with the season. In Ecclesiastes, Solomon writes, “To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven.” This is an all-inclusive statement, Blake. Seasons speak to sequence, of patterns, of rhythms in our life. It should be okay, therefore, for us to hit Pause, to slow down if we need to. To ask for help. To shift the load. To carry more or less as we need to, in order to do our share in that particular leg of the journey. Just finding that ebb and flow, the right crests in the troughs of the yin and yang and rhythms of life, but learning to do that in sync!

The third lesson I would share comes from Wayne Cordeiro, who wrote a great book called Leading on Empty, in which he shares his own personal story of burnout.

Blake: His name sounds familiar. Hawaii, right?

Ray: Huge church in Hawaii, and multiple churches in the Pacific or Southeast Asia, yes. He’s out jogging one day, and just completely collapses. He sits on the side of the sidewalk, just a few yards from his home, and bawls uncontrollably. He goes to the doctor, and they discover that a particular hormone is completely depleted. He has none. So, for six months, he retreats to a monastery, somewhere in Pennsylvania.

Blake: Just to restore his body.

Ray: To heal, and to find those rhythms again. In the process, he steps back and asks, “What’s the 5% that only I can do?” Not the 80, not the 15. The 5. And the 5 that he can do—that only he can do—is to be the husband to his wife, and the father to his kids. The rest, anyone else can do. I know this is a long-winded answer, but it concludes my third and final point, which is: We have to come to terms with what only we can do, and put the rest in perspective.

Blake: Very helpful, Ray. For Fixer Upper fans, I can’t help but think of Chip and Joanna Gaines signing off after season five, so they can focus more on being spouses to one another, to raising their kiddos, and to running their business empire and foundation. They agreed they could do three or four things, but not five.

Ray: With my kids, I build in time, whether it’s driving them around, dropping them off, picking them up. I search for opportunities to pour into my kids. With Nia, sometimes it’s a daddy-daughter date, where we can steal two to three hours together. Or helping her navigate a relationship at school, or reading a book together at night with Levi. I want to have meaningful conversations with my kids, and often they come up in the most unscripted ways.

Blake: Like what?

Ray: With Nia, lots will come up in our car rides together, and Levi, our son, he always has big Life Questions when it’s quiet and I’ve just turned out the lights! I just want to take advantage of those moments, be they special or ordinary, and make a parenting deposit. The same is true with Wendy. It’s important to make a deposit in the love bank, because that’s one of the ways I can be a good husband.

I’m also a believer in the power of margin, which I think each of us understands intuitively, but the execution of sabbath moments…of rest…of the 7th day…is something we have to be watchful about. I sometimes struggle with feeling lazy if I’m not busy, or like I’m a slacker or something, but margin—and rest—is Biblical. God created rest, and He demonstrated it Himself on the 7th day. Just resting and recovering.

Blake: Margin is a powerful concept.

Ray: I know, right? Just think about a car. Maybe a car is designed to reach 120 mph, but that doesn’t mean you drive it 120 mph all the time! And just because the stereo can reach 10 doesn’t mean you should listen to your stereo on 10 all the time; you’d blow out your speakers and your eardrums! Without margin, we’re tapped all the time. God designs systems to be self-sustaining, then He steps back from them. I think in our lives, too, we have to think strategically, and create a system that doesn’t require our hand seven days a week. Otherwise, even though we might be 100% busy, we’re probably not 100% productive or fruitful.

Blake: That’s a great segue to our final stretch together, Ray. Are you up for a few more questions?

Ray: Fire away, man.

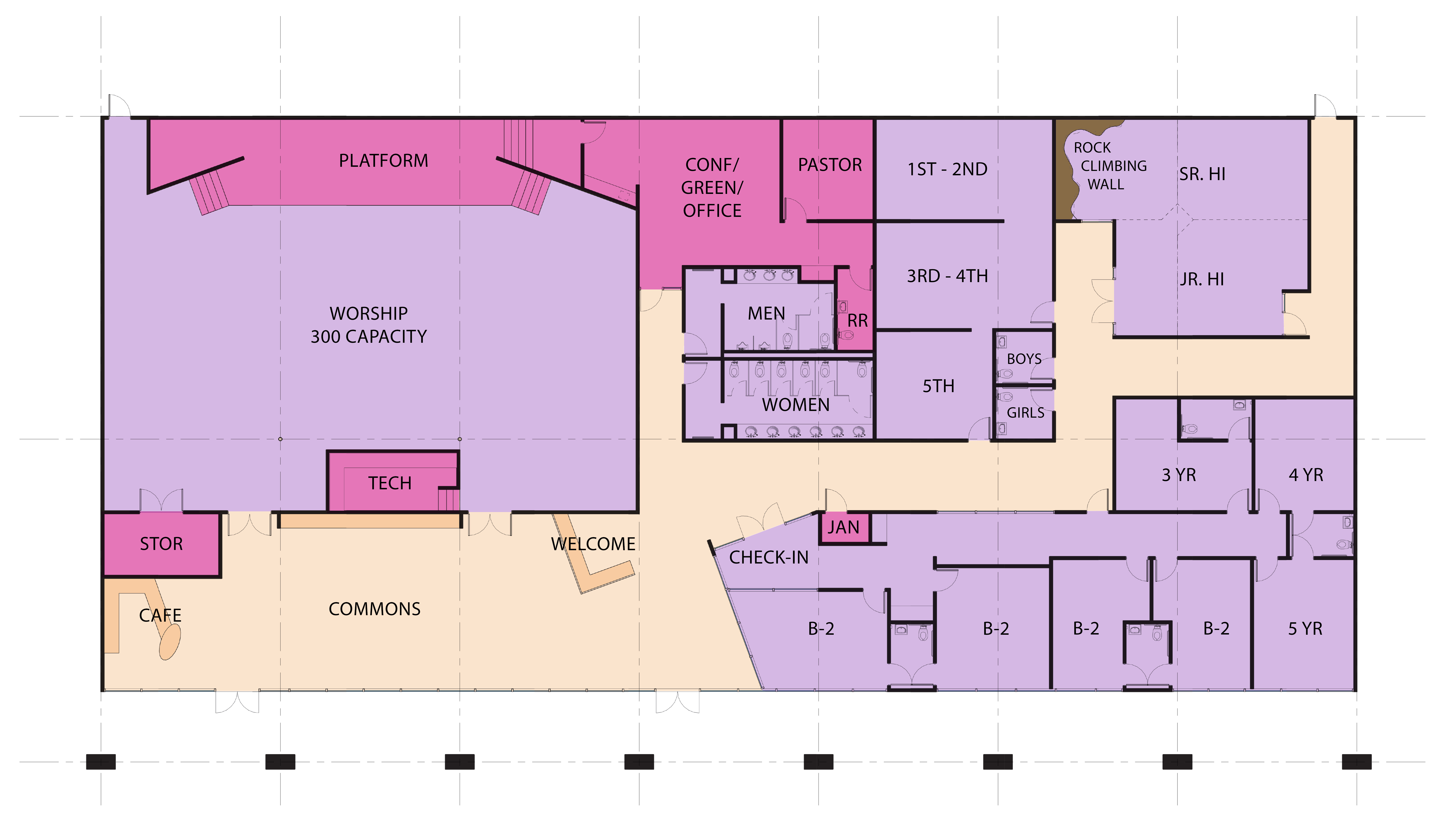

Blake: Talk to me about the future, and the future of City Church. What do you, Wendy, and the church’s leadership envision as the next season?

Ray: For nearly seven years, we’ve been portable—meeting Sundays in Angelika Film Center, in Plano. I’d say that for the first five or six years, we were portable by design; we wanted the church to run lean, financially, which made sense when we were launching. And that’s not unusual, either, to see a lot of churches that are portable and on the move. But what we’ve discovered in seven years is that our community hungers for more. More connection, more permanence, more presence. Churches typically fail if they don’t connect to families and kids, and more and more people are wanting a little bit more for their kids. So the next logical transition for us, Blake, is to find more permanent facilities where we don’t have to set up and tear down every week, which also creates huge fatigue and wear-and-tear on our volunteers.

Blake: Do you hope to stay in the same area?

Ray: In the heart of Legacy Town Center, near The Shops at Legacy, yes, which is an ambitious dream, but if God wants us to put our permanent roots down there, He’ll make it so. Plano’s mayor, Harry LaRosiliere, calls Legacy Town Center “the center of the universe,” because, as you know, Toyota just opened their North American headquarters there, JCPenney is there, Dr Pepper Snapple Group, FedEx, Liberty Mutual, and The Star—the Dallas Cowboys’ 91-acre campus and headquarters. More big corporations are moving into the area, which has driven up the cost of everything—off the charts. But God is already opening doors, showing us a footprint, bringing people to our congregation and to our mission.

Blake: Conceivably, and ironically, your church could be the heart of all of that, which is saying something. That could be huge, Ray.

Ray: We’re navigating how a life-giving church in the center of such a huge, international commercial district can find its place, and it’s going to require audacious, courageous leadership. When we felt the stirring, we began to pray, and it feels like heaven and earth are starting to move in our favor. An architect recently joined our church, a gentleman in his 70s, and he approached Wendy and me and said, “I think God has one more building in me.”

Blake: Oh, Ray, that is so powerful.

Ray: It’s huge. It’s the providence of God. There’s no other way to explain it. We are really feeling that our church is supposed to be an intersection of the secular and the sacred, of the ministry and the marketplace. It’s no accident that some of Jesus’ disciples were entrepreneurs; they were fishermen. Today, we don’t think of fishermen as CEOs or C-suite executives, but, in their day, yes, they were absolutely leaders in their communities. Some of the people that followed Jesus the closest, like Joseph of Arimathea, who gave his tomb for Jesus to be buried in…he was a similar leader in his community. The Bible is replete with this convergence of the secular and the sacred, and we believe that our footprint at Legacy will allow us to positively impact high-level leaders for the Kingdom of God.

Blake, I’m not a Corporate America guy, so I don’t know how all this will come to pass, but I can tell you that God is bringing people into our midst, people with skills and services and hearts for God, and doors are flinging wide open. Our part is to simply be obedient, and God will handle the outcome, whatever it is He wants. We’ll tackle the possible, and leave the impossible to The God Most High. We’ll build the ark; God will send the rain.

Blake: You know what I love about this Ray?

Ray: What?

Blake: You began our interview by sharing a really powerful experience, an experience in which your only path forward was to trust in God, to be obedient, to sit in the dark and pray. You committed your life to God in that moment, and what did He do? He brought the memory of your mom into the mind of a young man at a crossroads. The rebel that day could have been your executioner, but he was, instead, your liberator. And you know what made the difference? His memory of your kind mother near the marketplace. What you’re describing with City Church 2.0—the intersection of ministry and the marketplace—is a recreation of the very act that set you free.

Ray: Oh, Blake.

Blake: You profess to not be a corporate guy, but no matter, God’s put you in the marketplace, amidst the flow of commerce and connectors. He’ll sort out the rest, and it will flow. Your logo should be an orange, because it represents then and now, and the golden thread that connects you to your family, to acts of saving grace, and to the tremendous and transformational reverberations—eternal reverberations—that continue to emanate from one single act of kindness, paid forward, a transaction in a marketplace between a kind woman of means and another mother and her son.

Ray: I love it, man, way to connect some dots! There’s so much truth in that, so much truth. We’re still finding our way, our footing, for sure. We envision a gritty, urban, city-type environment.

I was studying my Bible recently and landed on the story of blind Bartimaeus, a beggar on the outskirts of Jericho. He’s at the gate, crying out to Jesus, and Jesus stops and ministers to him. Bartimaeus is begging for change in a cup, and Jesus ministers to him—right then and there, and gives him sight—and his life is radically transformed. News of Jesus’ miracle precedes him into the city of Jericho, where Jesus then runs into the chief tax collector, Zacchaeus. Zacchaeus is tiny, right, so he’s climbed up in a tree so he can see Jesus, and Jesus says to him, “Hey, Zacchaeus, come on down, man, I’m hanging out with you today,” and Zacchaeus’ life is similarly transformed. So the picture we have in our hearts for our church is that—whether you’re down and out like Bartimaeus, or you’re up and out like Zacchaeus—Jesus loves you all the same, and we wanna be that place where you can meet and encounter Jesus.

That’s the dream, Blake, and we truly believe the catalyst for it will be a facility that we can call His own, in the heart of the market.

Blake: It sounds like you’re seeing the first signs of fruit; it won’t be long before it’s a hustling, bustling ministry!

Ray: In God’s time; in God’s time.

Blake: I’ll be sure and visit when the tent turns into tapestries.

Ray: Oh man, we will roll out the red carpet and throw confetti for you, brother!

Blake: Ray, I’ve enjoyed our visit. We’ve covered lots of ground.

Ray: I hope it’s helpful, man, I hope it’s helpful. We’ve covered a lot, yes: defining moments, pain, courageous leadership, the works. Next up for us, as a church, is the purple cow.

Blake: The what?

Ray: The purple cow! Seth Godin tells a story about brown cows and black cows. You see ‘em all the time, and drive right by. But what if you saw a purple cow? Oh, man, you’d turn the car around, pull over to the side, hop out, and Instagram that thing! That’s what’s ahead for our church: to create something so special, so unique, right in the heart of Corporate America. Something that will turn people’s lives around, and direct ‘em right to God.

To learn the impetus behind Fireside, click here or here and please join us again next Wednesday for another chat.

###