FIRESIDE No. 13 with Dick Reynolds

Posted on November 29, 2017 by Blake Leath

"PERSEVERANCE,

LIFELONG LEARNING,

CAREER DIGNITY & PRIDE,

SCOUTING & SERVICE,

AND MENTORING"

l l l

I'm an organizational sociologist, strategist, writer, and teacher, but am—first, foremost, and always—a student of enterprises and those who lead them. In my 2007 book, Cultivating the Strategic Mind, I explored the transition from leader to visionary, creator, and architect of strategy. Today, I continue studying strategists and leaders but am increasingly haunted by what I see as a more fundamental, personal quest: understanding and improving the dying sub-disciplines of management, whether time, conflict, self, or life-management. Leadership gets a lot of glory, but management is the nuts & bolts practices of every day that gets it done. Fireside (which admittedly began as a series of ruminative 1 ½ to 2-hour one-on-one conversations with seasoned management executives reflecting on their life’s work) quickly evolved into dialogues about work within the context of life and life after work. This ricochet took me by surprise, but I found it an exceedingly pleasant one. After all, “Though we hire employees, we get people.” My sincerest hope now is that—in an oft-discouraging world—Fireside might prove a respite, a source of light, warmth, energy, encouragement, safety, nourishment, perhaps even inspiration in your own career or life, whether at home or out in the big, bad world. Around the fireside at the end of the day, it’s clear that we are all in this together, and everyone has a story worth sharing and hearing. You will be the ultimate arbiter, of course, but I predict we shall learn a great deal about management, yes, but even more about ourselves and this enterprise we call life.

l l l

Today's guest is Dick Reynolds.

Richard “Dick” Reynolds (retired) served as Chief Operating Officer, Chief Financial Officer, as Executive Vice President—Strategy Program Management, and on the Board of Directors for Libbey Inc., a world leader in the manufacture and distribution of tabletop glassware and other top-of-the-table products like flatware and vitrified china.

Dick integrated a virtually incomparable perspective of business and manufacturing financials with interpersonal savvy and organizational vision. As Libbey’s Chief Operating Officer and Lean Champion, Dick was the principal architect of the “Libbey Lean Enterprise,” implementing Lean thinking across global locations. As the company’s Chief Financial Officer, Dick led all aspects of internal and external financial reporting, financial analysis, treasury management, and investor relations. As EVP of Strategy Program Management, Dick focused on the development and execution of Libbey’s worldwide business strategy. Due to his broad, multi-functional experience, Dick has unique breadth, depth, and overall insight into management and leadership challenges.

Dick possesses more than 45 years of financial, operational, and strategic leadership. Throughout his career, he served as a mentor and coach to emerging leaders at all organizational levels. His natural ability to teach—combined with limitless energy and passion—makes him extraordinarily effective as a personal coach and role model to this day.

A lifelong Scout, Dick remains very active in the Erie Shores Council of the Boy Scouts of America as Scoutmaster and has held many positions on their board, including president. He also has served as a trustee for the Toledo Museum of Art, and as a board member of Imagination Station, a hands-on science center for youth.

Dick holds a BBA from the University of Cincinnati. He and his wife, Gloria, reside in Sylvania, Ohio.

Blake Leath: Thanks for joining us, Dick. I must confess you were one of our inspirations for this series. In recent years, we’ve been running into leader after leader who’s pursuing strategy and visioneering, but their direct reports complain they lack the fundamentals, like running meetings, setting priorities, handling conflict, deciding, delegating. You sent me a note several months ago that had the line, “I wish I would have learned earlier in my career that I am here to help others reach their potential by supporting, coaching, and challenging them to do things they never thought possible. I also wish I would have learned to ‘listen to learn rather than rebut’ at a much earlier point in my career.” I’m intrigued by this ‘advice to my younger self’ thing, so would you mind starting there? Specifically, what do you wish that you’d known earlier, and how much earlier, and why?

Dick Reynolds: It’s hard to determine when, but the earlier the better! I think I needed to have some background or time in the world, maybe 10-15 years, before I could even begin to comprehend some of the other stuff I was to learn later in life, and later in my business life. What I mean by that is: I was so focused on doing the what and trying to understand it, be proficient at it, develop a calendar for it, determine who was going to do what, learning to follow-up, learning the hard way that when you don’t follow-up you might get burned, learning too late that somebody hadn’t started working on the thing yet. Maybe after being burned so many times, I was embarrassed, and so I began to learn from these instances, and get more proactive, less reactive.

Blake: How did you pivot?

Dick: I gained more responsibility through those things, but I was a person who focused on how things worked, why they worked. When it came to people, I came across as a know-it-all, and that’s a terrible place to operate from because it stifles others’ ideas and input. They thought I already knew where we needed to go and why, so there was no reason for them to give any thought to it.

Blake: And it backfired?

Dick: It turned on me, yes. I could not get employees to collaborate on discussions of vision or strategy because they thought I knew so much more about the whole business that it shut them down before they even started.

Blake: What did you learn from this?

Dick: That I needed to start asking for their opinions and ideas, and sooner! And to share credit. I never wanted credit; I just wanted to get the job done. My father bred into me do everything to the best of your ability, and if you don’t get it right the first time, keep at it. The way I was raised, and time, and training—especially interpersonal training—opened my eyes to the importance of people, and the importance of striving to understand them.

Blake: Sounds like self-awareness was an early trigger, though.

Dick: It was the little things, like understanding that my desire to understand was interpreted as know-it-all. I didn’t know I had that moniker, and learning that I did was a big insight. I had just exceled, and with that came more responsibility, but as you move up, you get more isolated from people—which is the last thing you want to be. That was never my intention, but that’s part of what happens to each of us. And I didn’t get any management training until 1995, which was 25 years after I’d begun my career! I would sit in on those classes and just think to myself, “Wow.”

Blake: What was your reaction?

Dick: Boy, I need this! I need more of this! But it was difficult, too, because I had to unwind so much of what I’d learned the hard way for so many years. My boss once said, “Dick, you don’t need this training,” but I knew I did. The world is changing, people are changing, and we needed to get more out of them than just their arms and legs. We needed their hearts and minds engaged. I’d get into wrestling matches with my boss about my attending, but I found the training revelatory.

Blake: What, in particular?

Dick: I learned to treat people consistently, but uniquely. I learned how to treat people differently based on their own experience level, their personality, their style. I learned when to dive in, and when to let go. I learned how to orchestrate change—and purposefully, strategically, across a time horizon. There’s a funny line from a book I read during this time: “Change is good. You go first.” That’s so true! Getting a hold of that, and things like that, set me on a path of learning that continues to this day, even in my capacity as a volunteer.

Blake: Did your boss become more supportive after he began seeing results, or a change in you?

Dick: A lot of people thought I always got what I wanted from him, but I don’t think that’s true of anyone. We never get everything we want. But I did learn how to improve my requests and suggestions, to meet him at his style, to sequence things the right way to decrease the likelihood of hearing no. He had a funny saying: “Dick, your vote and my vote are the same, but mine counts a little bit more than yours.”

Blake: How true. Everyone’s equal, until they’re not.

Dick: I learned the importance of vision, of storytelling, of having a compelling story that helped people understand where they fit in, and to what end. In a lot of these management training workshops, we—as officers—would have the opportunity at the end of day two to come in, sit in front of a class, read their flipcharts, and field questions. I found those experiences tremendously rewarding, because it gave us an opportunity to address what was on their minds, not on our minds. As an executive, you’re often conveying what’s on your mind, but I think that’s backward. Until you know what employees are thinking, worrying about, struggling with, wanting…you don’t know how to best support them, or help them win. The biggest successes I ever experienced in my career were those that were egalitarian, driven from and believed in from the bottom up. The least effective were management dictated.

Blake: I think that’s a keen insight. How did you apply this?

Dick: Ask people for the pains; ask them to help modify the process. Give them opportunities to do so, through time and funding and methodology. Encourage them to speak up, and allow them to. When employees tell you why things are stupid and don’t work, listen to them! They are the ones doing the work, and they are the ones most qualified to improve it. This is what got me to listen to learn versus listening to rebut. Changing my perspective was a huge epiphany. One of my favorite statements now is, “Tell me more about that. I’m intrigued…tell me more.” It builds trust, and improves understanding. One of the biggest mistakes anyone can make is to underestimate someone else. Or to be in business for ourselves, and not the benefit of the whole.

Blake: I know that trust is a huge part of this. Really believing someone’s intent. And in we/they environments, particularly union vs. management, trust issues are huge impediments.

Dick: There’s an unwillingness to change the rules, yes. But think about streetcars. They went out of business because the rails in the road became limitations. Too controlling, and travelers wanted flexibility. The rails only allowed people to go where the rails went, so trying to overcome such things and build more flexible relationships is essential to survival. Unfortunately, in really broken relationships, people’s intents are misconstrued. “I’m really trying to listen here,” but they just think you’re schmoozing, greasing their skids, etc.

So all of this, Blake, the learning, the listening, the understanding of individual and organizational phases, of style, of putting people before process, of engaging hearts and minds to orchestrate change…it led to happier, more productive employees. We acknowledged people, thanked them sincerely for their contributions, engaged them more often when setting direction. Now, unfortunately, pay and compensation often become a stumbling block because people—no matter how significant or insignificant the gap—perceive only disparity and unfairness, and I don’t know how to solve that. Chalk it up to market forces and economics of the world.

Blake: Socialism has tried, but only meritocratic/pay-for-performance organizations thrive. Without proper incentives, the best and brightest boogie on. You’ve touched on a lot of great stuff, though, Dick, so in addition to what I’ve already mentioned, you’ve also reminded us the importance of acknowledgment and thankfulness, so thank you for that!

You know, every Christmas we watch Scrooge with Albert Finney. It’s one of my favorites. When Scrooge has the opportunity to look back at his life and see how he treated people, he cringes. When you look back at your 20s and 30s, does anything make you cringe? What would you whisper to your younger self?

Dick: Yeah, there were situations where I ended up firing people. Pretty summarily, in many respects (not that I didn’t feel I was justified), but I hadn't given the person feedback that they weren't doing well, other than indirectly. And so I was not coaching them to where I thought they needed to be. I was more like, “Okay, if that's all you're going to do, and I'm expecting more, whatever. You don't get things done on time, and you never do, and you don't seem to care that you do or you don't, so I’m letting you go. Now.” Letting people go was the toughest thing I ever did in my career. It’s an uncomfortable feeling to sit in judgment of someone, to—in effect—reject their behavior, and know what tremendous collateral damage it will have in their life, and the life of their family. I hated it. Just hated it.

Blake: But don’t you find that sometimes you’re doing them a favor? Sure, maybe there’s a less painful way to arrive at their exit, but I often find that some people are underperforming because their heart’s not in it, and sometimes their heart is not in it because there’s a better job waiting for them somewhere else, and they can smell it.

Dick: It is true. I’ve had a couple people come back to me and thank me for firing them, but it took three to four years for that to happen. I’ve always appreciated it when they’ve come back. But the way I treated people early in my career, with follow-up/follow-up/follow-up, was more a hammer than a helping hand, and it upsets me to this day, and bothers me. I regret it, but cannot change it, other than to learn from it, which I hope I have.

Blake: We’ve talked a lot about whispers to your younger self, but I’d like to know more about your career trajectory. Can you talk to us about your journey a bit?

Dick: Okay. I went to school originally at Miami University, and I went there for pre-engineering, because that's what my dad wanted me to do. I started out that way, with a focus in chemistry. I flunked out after my first year, and then went to University of Cincinnati, and went into design, art & architecture, which was what I thought I would like to do because I loved drawing and I loved buildings and all that kind of stuff. For a year, I worked full-time during the day and studied this at night school. And then Gloria and I got married. The DA&A program was a six-year program, and I knew I could not spend another five or more years in school, so I switched over to business with a major in finance. In 1970, I graduated with a degree in finance. Coming out of University of Cincinnati, I interviewed with Owens-Illinois and took a job there as a Comptroller trainee.

I went to work with them at the plant in Toledo, transitioned from that initial financial position to Cost Supervisor, got a six-month stint in the factory as a Frontline Supervisor, which was a seven-day/rotating shifts position. It was a hard job, but tremendously rewarding because we were in it elbow-to-elbow, and I got to see first-hand what people were doing and trying to create. It was an invaluable opportunity, and very helpful to my learning.

I came out of that job and became Comptroller there, then I went to Shreveport, Louisiana, as Administrative Manager, so I had Finance, Industrial Engineering, Purchasing, Customer Service, and Information Technology. I eventually returned to Toledo as Manager in Production Planning & Distribution for the Libbey Division.

At the end of that, 1993, Libbey got spun-off from Owens-Illinois and I became Chief Financial Officer, so I was able to participate with [CEO] John Meier to take the company public, which was rewarding and challenging. Raising capital and truly running a business is much harder than simply reporting to a mega corporation! After two years as CFO, I became Chief Operating Officer, because my true love was really Operations. At that point, I was responsible for Sales, Libbey’s plants, and Engineering. I did that until 2011, then became CFO again, and eventually retired in 2013 after 44 years.

Blake: I’m curious about your initial interests. Did you ever regret abandoning Design, Art & Architecture, or did you find your work at Libbey fulfilling?

Dick: I guess I have a couple responses to that. On the one hand, my dad was pretty hard on me. When I graduated, Dad asked, “What makes you think anyone’s gonna hire you?” The way he put it, I didn’t feel like I was worth much. It was a downer, but that’s the way he was. It was hard living up to a graduate of MIT. In the first six weeks, yeah, I was probably thinking, “What have I gotten myself into?” but that’s because it was so overwhelming. But I’d been raised to give it everything I’ve got, so I put my head down and just plugged away. I put the business principles to work and began to learn how we made products. The more people realized I wasn’t just someone up front counting beans, the more they respected me and opened up. I think Design, Art & Architecture is a great field, but there are also a lot of starving artists and architects out there struggling to support their families, so no—I didn’t regret it at all.

I’m glad I switched to business and finance, and not accounting, because I enjoyed the variety, the analysis, really digging in and understanding how the business worked, made money, lost money.

That may be a long-winded answer to your question, but no—I don’t regret anything about the choices I made or the career I lived.

Blake: Thank you for that. I’m sure there are a lot of people who are thankful for that, and for your leadership at Libbey. We can return to Libbey in a moment, but can you talk to us a bit about Boy Scouts? I know scouting has been a large part of your life for a very long time, so I’d like to understand what got you interested in the first place, and what you do there today.

Dick: Yeah, I started in scouting as soon as I was eligible, which was in 1956, when I turned eight. I joined at my church, went through Cub Scouts then Boy Scouts, from 8 through 17. At Miami University, I was not involved, but when I went to University of Cincinnati, my old scout troop was struggling with leadership, and I stepped in to be Assistant Scoutmaster at maybe 19-20 years old, because you can’t be Scoutmaster until you’re 21. I really ran it, and was sort of sponsored by the other adult in the room.

Blake: What has scouting taught you?

Dick: So much! These were formative years, so I learned a lot about my own opinions on leadership. I was a Patrol Leader, then Senior Patrol Leader, and each of those roles has an assistant, so you learn more and more responsibility to help the scouts below you. We were an active troop, doing at least one outdoor thing each month, whether camping, canoeing, hiking, whatnot. I was also active in high school football, and baseball with the church, so I was always busy and engaged. When I began interviewing for Owens-Illinois, it mattered to people that I’d spent so much time trying to lead young men, and hopefully to do the right things. I had already learned quite a bit about planning, conferences, processes, pressure, discipline.

Blake: Did you achieve Eagle Scout?

Dick: I was fortunate enough to do so, yes, and I hold it as one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. That, marriage, parenting, and taking Libbey public. Those four things are the high watermarks of my life.

Blake: What does scouting offer young people today?

Dick: The outdoors, skill development, building things, enjoying nature…really treasuring it, appreciating it, understanding it. Character development, understanding seasons, eternity, people, life, growth, death, the cycles of life. Nature is a wonderful teacher. And values, morals, role models, work ethic. Sometimes, when I go to a baseball game—let’s say with 6th or 7th grade kids—and I see parents screaming at umpires, I reflect back on all my many wonderful role models, and I grieve for these kids. I so firmly believe in the values of scouting—of learning from, working alongside, absorbing lessons from peers and other adult role models. It was such a fun, safe environment, and it breaks my heart to see young men and women who’ve never experienced that.

As an Eagle Scout, you pledge to give back to others, to give them the same opportunity. We view ourselves as “marked men,” and would never deface the marking of an Eagle Scout. That’s not to say we’re perfect, but I know we strive to live an adult life that includes service and integrity.

Blake: Was your son involved in scouting?

Dick: He was, and it allowed him to blossom. He became more extroverted, and took on more responsibility. I just can’t say enough great things about him. I think scouting is an outstanding program for young people.

Blake: And today? What’s your involvement with it today?

Dick: This past summer we ran a summer camp with 105 staff members, and the staff ranged from ages 14 to 72, male and female. We talked to the staff beforehand about the importance of customer service, and how, because it’s an attitude—not a department—we’re all in the customer service business. The scouts are our customers, as are their parents. We also talked about how important it is to treat one another well, because we’re role modeling for the scouts, and though they’re there to learn skills, it’s also a great opportunity for them to see how healthy, well-adjusted adults and young staff members interact with each other.

Blake: How long have you been involved in this summer camp, in particular?

Dick: Fifteen years. I used to use a vacation day to do it, but now that I’m retired, I’m there all week. I walk around, visit with campsites, and gather feedback. “What can we do to make your camp experience better?” The feedback is all good, but I pester and say, “We appreciate that, but what can we do to make it better?” The more you dig, the more you find. I then share that feedback in an effort to improve all the campsites, and the entire experience for everyone. Sometimes it’s simple stuff, like, “Make eye contact. Say hello to everyone you pass along the trail. Ask, ‘How are you? How’s it going today?’” These are things that are transferable to any workplace, by the way, and which are free, and which shape a positive culture.

Blake: I would say common courtesies and common sense are less and less common. Hopefully by role modeling it—these intrinsic things—every staffer and scout will come to look for these things in future employers, and to emulate them in the big beyond.

Dick: We don’t pay them [the staffers] a lot of money. Mostly, we feed them and give them a place to sleep, so you’re right, most of what they get out of it is intrinsic, and it’s very motivating.

Blake: Maslow and Herzberg would agree. Once the physiological, safety, and hygiene needs are met—in this case, base pay, food, and sleep—the real motivators are intrinsic anyway. This is a huge problem for most organizations, who fill bottomless holes with extrinsic motivators like cash and cars, while treating people deplorably across dimensions that are free and wildly motivating, like inclusion, purpose, meaning, acknowledgement, affirmation, empowerment, trust, connection.

Dick: Swimming is a good example of that. We literally teach scouts to swim, without which they could drown! But after learning to swim, it’s the encouragement they receive and the fun they have that brings smiles to their faces. It’s a very rewarding experience. We offer 85 merit badges or, as I like to say, “Eighty-five chances to expose kids to things they may not get exposed to elsewhere to try and determine what they ought to be doing for their career.” The more they experience, the more they may say, “Oh man, this is cool. Can I come on staff and teach this?” It draws young people into a positive experience, and young people are our future. There are so many challenges facing them these days that it’s nice to be part of something positive that might help them feel safer, better, more secure in themselves and the world they live in.

Character development is a huge part of it, and the right kind of citizenship—active citizenship—and a positive focus on a supreme being. We don’t force religion on them, but we model reverence. These things are important, because nature and animals and we wouldn’t exist without our God, so that’s what draws me back to it again and again, and why I’ll continue to do it.

Blake: What’s the origin of Boy Scouts?

Dick: It goes back to England, a gentleman named Lord Baden-Powell. He was a military commander who retired and started up an organization for young men so they could learn skills about survival and taking care of themselves and how to cook all these kinds of things. It wasn't militaristic but, rather, was based on skill-development and exposing young men to a more positive environment. It began in 1907, made its way to the U.S. in 1910, and though Baden-Powell was certainly the founding father of it, lots of people grabbed onto it here in the USA, led the charge, and it’s flourished.

Blake: Talk a bit more about being an Eagle Scout. Many of us have heard about it our whole lives. What makes it so special? For those of us who are not indoctrinated, please explain.

Dick: To some extent, I liken it to a college degree. What do I mean by that? For starters, it’s a long-term goal. It takes on the order of three years, not six months. At the end of three years or so, it’s sort of like being ‘academically able.’ You’ve passed all the requirements, but it doesn’t mean you’re practicing it yet. A lot of people have the designation, but they don’t practice it. To get there, you’ve had to proceed through all the ranks of scouting. Tenderfoot, Second Class, First Class, Life, and then Eagle. You also have to serve in some leadership positions in your troop. That doesn’t mean you’re necessarily successful at it, but you’ve served and are moving along. The last thing for Eagles to do is a service project. Projects are substantial. For example, you have to plan and execute an entire project that utilizes others. If that requires raising money, you raise money. The project cannot be for scouting. It has to be for the community, or school, or church, or a nursing home, or a park, something like that. Anything that is not for the scouting movement itself. So you have to seek approval for the project, and it has to be substantive.

All this requires interfacing with decision-makers in the public sphere. After the project, you go through a board review, which includes people from beyond your troop…from inside a district, which is a much bigger area. The district may have 80 troops in it. It’s not an interrogation, but it’s important, so they really review your project’s performance thoroughly. The process can be intimidating, at least for a young person, but it draws lots of kids out of their shells, helps shy kids overcome their introversion, and it’s meant to be a very positive, rewarding experience.

I joined Cub Scouts at eight years old, Boy Scouts at 11, and became an Eagle Scout at 16, so it took me five years to get there. Every troop has Courts of Honor, where you are presented with your rank advancement, or after you’ve earned a merit badge and so forth. The parents are there, you go up on stage, people describe what you did, you get the badge, you sit down. One summer, I must have been 14-15, and I’d spent my entire summer camp teaching 17, maybe 18 scouts from my troop all kinds of scouting skills, whether tying knots, lashing poles, or how to work a rowboat. The boys did marvelously well in terms of advancement, and every single one of them was recognized at the Court of Honor…and I didn’t get recognized at all because I hadn’t gone through the process of signing up for a merit badge, meeting with a counselor, etc.! None of that was in my DNA. At the Court of Honor, I was really disappointed—as were my parents, who made that clear—but I was also proud, because I’d spent my entire summer focusing on others, not myself.

Blake: Dick, as you work with young men and scouts today, are you making any observations about societal or generational changes, or is there anything you see today that's the same or different than it was perhaps when you started?

Dick: I am starting to see some of that, yes. Many of the younger kids that are scouts themselves, well, they are almost of the mindset if I show up and sit through a class, I deserve the badge. I deserve to get that because I paid my money to come to camp and so therefore I should get this badge or that badge. It's kind of like I paid up and I showed up, so therefore you should give it to me. To me, Blake, that is not fulfilling the promise. I see similar behavior with 30-40% of first-year staffers who’ve never been on staff and don’t know what to expect. When they realize this is hard work, they’re tired, or they hate it, they try and find ways out of it. We tell them, “You’ve committed to this; it’s important we deliver on our promise…which is to give the scouts a super camp experience—one that creates memories—and you’re going to create memories by how you make them feel. We want them to leave thinking this was a mountaintop experience, and for them to carry that home to Mom and Dad and to remember for the rest of their life.” A great experience is what keeps kids coming back for more, but sometimes staffers act like I’d rather be playing euchre or gaga ball or doing whatever rather than teaching this skill or class I’m supposed to be teaching. When we experience this, remember, we are role models for the role models, so we shouldn’t go chew some staffer out! Instead, we should view it as a coachable moment, seek to understand, try to find the why, then coach ‘em up to expectations…what we expect, what the camper expects, what the parents expect. But yeah, these things are tougher today. There’s a little bit more entitlement mentality. They’d rather be on their iPhone than dialoging with people sitting right beside them.

Blake: Present, but elsewhere.

Dick: You can’t fix it in that moment, but when you come alongside them on a project, you can ask, “Where do you go to school? What brought you here?” You know, just let them know that you see them, that you care, that you are interested in them as a human being, rather than a staff member.

Blake: “We hire employees, but people show up.”

Dick: And once we tap into their passion, they’re unstoppable. They go at it with everything they’ve got. But yes, it’s more difficult today than it was. Even my son says to me, “They’re different than we were, Dad.” Neither side can stay in their own world. We have to find common ground. A closed fist won’t work; we have to extend an open hand. Figure out how to learn from each other. The worst thing you can do is say, “Back in my day… .” Kids don’t want to hear that; they’ll just tune you out or turn you off. So it comes back to having fun, learning about character and values, sometimes without their knowing that’s what we’re doing!

Blake: Two final questions about Eagle Scouts, then we can move on. First, what’s the average age? And second, what percentage of scouts earn it?

Dick: Most are 16-18 years old, and fewer than 2% earn it. Lots of scouts are Life scouts, the stage right before Eagle, and they wear that t-shirt. I’ll say to them, “Hey, that’s great, you’re a Life scout! When are you going to become Eagle?” “Oh, some time next year,” they’ll say. But they have no plan. You gotta have a plan! So we have that discussion, because once you turn 18, you’re ineligible. The window has closed. I say, “The fumes will get in your way,” and they ask, “What fumes?” “Perfumes and car fumes.” Teens get distracted, and that’s understandable, but they always think there’s more time, and we all know that time flies by. I work with lots of kids, and of those who attain Eagle, tons of ‘em accomplish it just a couple months shy of their 18th birthday. Whether it’s girls, cars, sports, or having never thought backward from Eagle to think what project, what merit badges…they just wait too late, and then it’s over.

It’s perfectly fine for other things to be more important in life, but when I talk about being an Eagle Scout, I tell people I got my first job at Owens-Illinois because I told the interviewer I was an Eagle Scout. It meant a great deal to him—he told me that after he’d hired me—equating it to a college degree. You put an objective out there, you work to reach it, you stay focused, you’re disciplined, you show accountability, you get it done and knock it outta the park.

You can theoretically become an Eagle at 13. There are time requirements after each rank…you gotta wait one month, then two months, then six months, but I think at 13 you can become an Eagle. Application of what you learn and experience is where real learning begins. This takes time—applying and teaching others. But a whiz-kid who rushes through it is the same as someone who’s book smart, but not life smart. There are a lot of people out there who are good workers, or cerebral, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re successes in life. They don’t understand what it means in the world.

Blake: Knowing these experiences—from scouting through Owens-Illinois to Libbey and working with young people today—what advice do you have for us as mentors? Specifically, if you were mentoring a twenty-something, what would you suggest they know or do or be to be a more effective manager?

Dick: I’d start with the importance of trust, and share that trust is something to be earned. Getting to know your employees is key, and their knowing that you truly care about them as people. Listening to learn, understanding their circumstances, their situation, getting them to open up and share with you. Ask your employees, “What would you like to be doing, whether in your job or career? How do you want to be developed? Where do you want to be better?” Talk with them as much as you can, and encourage them to not close any doors that they don’t have to.

I, for example, was a finance major who wound up working seven-day rotating shifts on a production floor. Over the years, I transferred through nearly every nook and cranny of the business, which helped me to see and appreciate how it was all tied together. Be inquisitive. Develop contacts and context. Observe. Ask how things fit together. See the people dynamics, the processes, the puzzle pieces. Show that you’re interested and increasingly knowledgeable, and this will build your credibility and open all sorts of doors.

Blake: You practiced what you preach, Dick, and that’s to be commended.

Dick: In my final couple years at Libbey, I was mentoring people in Engineering, Production, Sales, Finance. We’d pick a subject that wasn’t their subject, whether drilling into the P&L or whatever. Nothing overcomplicated, and always in baseball language—language we can all understand. Figure out what the business is trying to achieve, and how to get there. I always approached it from a disposition of helpfulness, of wanting to help them succeed. When you’re mentoring someone, you’re trying to educate them, to encourage them, to build rapport and trust with them, to help them be greater. They need to know where they fit into the puzzle, and the importance of the various concepts in the business. Things they probably have never been exposed to, such as, “If you’re an engineer, and you want to be a leader in this company, learn where capital comes from, how projects get authorized, who does what and how.” As an engineer, for example, you understand projects, but may not understand how they germinate, or how they get ‘graded’ by executives.

I always encourage engineers to spend time on the floor, in the factory, operating. See how a forming machine works, how the design studio decides the next best thing, how a machine transforms that idea into a successful product that Sales can sell. Get input, gather people together, develop and test theories. Listen, learn, and don’t believe ‘by the book’ means gospel.

Blake: The difference between book smarts and real-world applicability.

Dick: Right. Too many people will fall back on, “Well, the book says we gotta do it this way,” and I say, “Yeah, I understand, but who wrote the books? People did! Let’s improve things, then we can write new and better books that future employees can improve upon, too!”

The mentoring relationship itself evolves and changes. At the beginning, a manager owns the process, but then the protégé or ‘mentee’ needs to. “Next time we get together,” I say, “you set it up. You set the agenda.” They have to own their own development; I can’t own their career for them.

Blake: Interesting. A lot of what you’ve just described is how you described scouting. Folks have to put in the time, some things can’t be rushed, they have to be a learner, be open, engaged, ask questions, build relationships, earn trust…and all these things don’t happen overnight. There is a time requirement.

Dick: A great career is the project of a lifetime.

Blake: I love that. The difference between a Life scout and an Eagle scout is those few extra steps, and one great project.

Dick: Part of which requires feedback, and feedback is a gift. It can be intimidating, but again, it’s meant to be positive and rewarding. Some people—in the course of scouting or their career—may come across as critical, but if you consider feedback a gift, you’ll see it as something helpful to you…and embrace it. That’s not to say all feedback is appropriate, accurate, or on-point, but again, we hear it, we glean what we can from it, we plan and improve and move forward.

Blake: It’s also interesting that, in the same way ‘kids these days’ might want instant gratification, you witnessed Libbey go public, and long-term plans became subservient to shareholders’ focus on 90-day plans! That’s a whole different world, where people are wanting returns on their investment now, now, now. I bet for a somewhat sleepy company going through growth pains, that was a wake-up call. A “cold shower” as I’ve heard it described.

Dick: That’s exactly right! There’s quarterly pressure, and that’s not dissimilar from a young person starting his or her career and expecting to be a manager in three years, a leader in five, an executive in seven. It’s a lot of pressure, and not particularly realistic, at least not in most large organizations.

Blake: I do worry about kids who see founders of Facebook, PayPal, Snapchat, Tesla as their role models, versus a parent who leaned their ladder against the same building for 40 years. It’s no different than a high-school athlete who expects to go pro. God bless ‘em, but the odds are against ‘em, and they may be setting themselves up for a horrible disappointment without really understanding how things work.

Dick: It’s amazing. You’re absolutely dead on. I’m not moving fast enough here, they think. I once mentored a new hire who said, “If I’m not running this place in three years, I’m outta here.” I said, “That’s a great objective, but why three years? Do you even understand all the terrain you’d need to cover in that amount of time to be qualified?” He just had unrealistic expectations.

I was rather naïve myself. I remember one of the first questions the Comptroller at the plant asked me. “What’s your objective?” “I’d like your job in three years,” I said, no idea what was coming out of my mouth or how he must have perceived it! [Laughter] I just felt the pressure to say something, so I did…without giving it any thought whatsoever!

Blake: How did he respond?

Dick: Oh, I don’t know. Probably, who is this guy? And if you become Comptroller in three years, what will you do the 37 years after that? [Laughter]

Blake: I think when we’re young we don’t appreciate or value the network, the web of connections, how everything—and everyone—fits together.

Dick: That’s exactly right. It’s about the connections to people, and how may I be of service. When we’re young, it’s all about ‘me.’ And our culture is doing us no favors on that front. We’re just immersed in this water of Kim Kardashian’s over here doing this, and Jennifer Lopez is over there doing that, and this fella at Uber and Apple made billions doing this other thing, so when do I get mine? Their frames of reference are so warped; it’s very unrealistic. To think that in any other place beside the tech sector these things are even possible, much less probable…it’s just such an infrequent success story, to be Steve Jobs or whomever.

Blake: Every little leaguer expects to play for the pros. I saw something the other day. There are eight million student athletes in the United States, of which 480,000 will play college. Of those, 1-2% will play pro. The highest was 9%, for baseball. But for soccer, football, basketball, no more than 2% of college kids play pro. Hockey was 5%.

Dick: Tough odds. And more wash out after their first year or season.

Blake: My heart goes out to kids, because as adults—particularly as parents—we want to encourage them, not dash their dreams, but we also need them to be realistic. To not sell them a lie. Because by their late 20s, they’ll think, “I haven’t accomplished these things. I’m a failure.” Their self-talk is really sabotaging and undermining, and because they’ve won participation trophies their whole lives, they never developed the mechanisms and mental muscles to rebound, to bounce and not break. Then, they drop out, or quit on life. And for most of us, life was not a bed of roses; it took a decade or two just to find our line and tack toward it. To say nothing of self-destructive coping mechanisms, or lashing out, or substance abuse…all the ills and ales that ail.

Dick: That's one of the things I believe scouting teaches: self-worth. You don’t have to be the best, or the best at this skill. Not everyone is the best, but you do need to demonstrate proficiency, or mastery, or have fun working at it. You’ll find something in those 85 or 135 merit badges that gets you passionate. It’ll focus your energy, and your time, and could very well become a hobby or a vocation, and that’s wonderful.

As you say, some young employees don’t [in their minds] succeed, which gets them down, and then they wind-up becoming adults that someone has to care for the rest of their lives.

Blake: Failure to launch. I’ve coached or mentored a lot of prima donnas who thought they were going to own the world by 32, and when that didn’t happen they withdrew from life. They can be found at home…waiting for the perfect job to come along. They’re rather unemployable, because whatever skills they had are now rotting on the vine.

Dick: Unfortunately, I see a lot of that, too. I see it.

Blake: I’ll conclude my part with an observation. You described, as a finance major, the importance of working shifts on the floor. I can’t help but think of that as your own merit badge. The journey you took throughout your entire career mirrors the skills one endeavors to master as an Eagle Scout. The older I get, the clearer it is to me that there is nobility is simply enduring. Stick-to-it-iveness alone is honorable and virtuous. To return to work, be it a cubicle farm or a coal mine—day after day or shift after shift—with a great attitude, engaged, participative, thoughtful, and kind to others, is to be revered. That, to me, is the end game. It’s not to become Steve Jobs. It’s to do the often unglamorous, and to do it as if someone were watching—even when they’re not. That sort of work ethic can be found in every successful organization that sustains, is what this country is built on, and is what will be required for the future.

I think a lot of us, especially when we’re young, get seduced, deluded, distracted by the sizzle and sex appeal of some utopian job that’s out there, just waiting for us, right around the next bend. It’s a nice dream, but legions of people, the vast majority of them—from farmers and laborers to mechanics and first-responders and struggling artists who remind us the importance of beauty—make everything function, and possible, and worth doing.

I know you know all this, but I just wanted to share it.

Dick: I agree 100%, and I appreciate your sharing that. There is a lot of overlap, to be sure, and work is an important part of life. Speaking of work, I hear some chores calling.

Blake: No worries, Boy Scout. Hey, thank you for your time, Dick. I’ve enjoyed it and know a lot of people will benefit from reading it.

Dick: Thank you. Great visit. Time now to go chainsaw.

E N D

Morning flags at Pioneer Scout

Reservation Summer Camp. We host

approximately 500 scouts, drawn

from many states, for each of

the seven weeks.

A first-year scout—and truly happy

camper—who caught his first fish

(setting the camp record

for the week in terms of

length and weight).

Human Foosball court where

Troops challenge each other to

blow off steam and have fun.

Tomahawk throwing at Erie Shores

Council camp celebrating 100 years.

Working with two other retirees, we

replaced a bridge at Pioneer Scout

Reservation and upgraded

the trail for wheel chairs. We built

the bridge to accommodate

these kinds of vehicles in

case of emergencies.

Summer camp staff working to fill in the

sand and stone between the railroad

ties to connect the boardwalks.

Two retirees and I built in camp about

one half-mile of boardwalk, and the

scouts will fill in between with sand as a

summer service project for the camp.

(Pictured here are staff members

practicing what they are to

teach scouts to do so that it

remains strong and survives the

four seasons for decades to come.)

Adding 280' of boardwalks at Pioneer

Scout Reservation camp so Scouts and

adults with disabilities can get out into

the woods. This particular boardwalk

covers many very wet spots with steps

leading up to a Showerhouse.

Ecology Pioneer Scout Reservation

Summer Camp staff. They teach 26

merit badges for seven weeks

each summer.

WoodBadge Patrol, for whom I served

as coach and Patrol Guide in 1992.

WoodBadge is all about leadership

training for adults in Scouting.

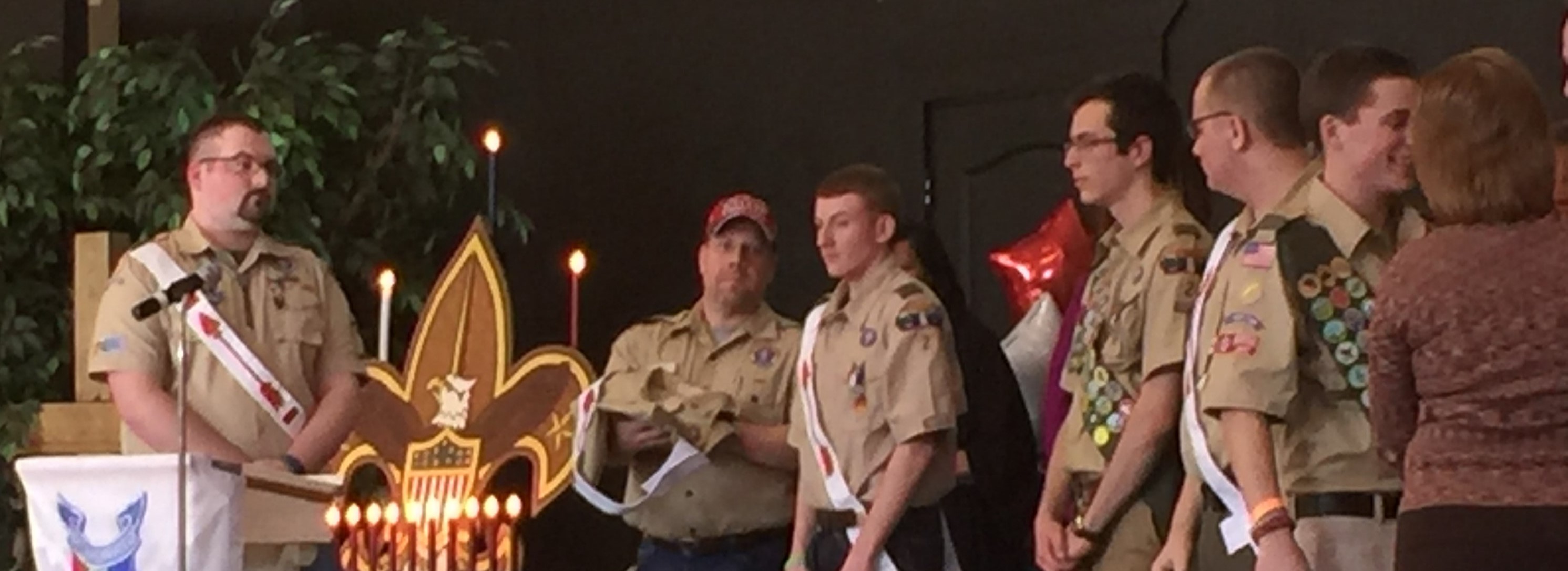

Three young men receiving their Eagle

Rank Award at a Court of Honor of the

Troop where I was Scoutmaster

25 years prior.

Picture of Marblehead Harbor in

Massachusetts where my parents

grew up. We travel to the East Coast

every year to research genealogy of

our families. I am an 11th Generation

descendant of Robert Adams,

who arrived here in 1635.

Exploring many castles in Wales with

my wife. Since 1992, my wife and

daughter have gone to the UK

every year for a two-week stint

exploring castles and English history.

My wife and I are annual Pass holders

at Disneyworld, where we enjoy rides

and people-watching! We enjoy seeing

kids and their families have a great time.

Here I am with Goofy, which

my wife says is fitting.

Giant Redwoods in Sequoia National

Park. General Sherman is a giant

sequoia tree located in the Giant

Forest of Sequoia National Park

in Tulare County, in California.

By volume, it is the largest known

living single stem tree on Earth.

My wife and I hiking the many trails

of Muir Woods on our

50th wedding anniversary.

To learn the impetus behind Fireside, click here or here, and please join us again next Wednesday for another chat.

###